Confronting Inequality in the UK Pension System

A Call for Fair and Lasting Reform

by Anthony Royd

Article 4: The Triple Lock Controversy

Published 6th December 2024

In previous articles on the UK State Pension, Anthony Royd explored inequalities within the state pension funding structure, including the adverse impact of pension increases on means-tested benefits and other disparities in state pension provision.

The comparisons between public and private sector pensions raised ethical questions about the fairness of funding public sector advantages through private sector taxation.

This article delves into the complexities of the Triple Lock system, analysing its benefits, criticisms, and how it compares to pension models in other nations. It evaluates the Triple Lock’s role in addressing relative poverty and explores effective alternatives to achieve pension adequacy while ensuring fiscal sustainability.

Prior to the introduction of the Triple Lock in 2010, UK state pensions were widely criticised for their inadequacy. Over decades, the basic state pension failed to keep pace with earnings growth or inflation, exacerbating concerns about poverty among retirees.

In 2008, the basic state pension represented just 30% of average earnings—a figure already low compared to many other developed nations.

Despite the introduction of the Triple Lock aimed at improving pension adequacy, the full new state pension now stands at just below 34% of full-time mean earnings and is projected to fall below 30%. This failure to make any significant improvement in sixteen years, underscores the system’s failure to meet its target and raises serious questions about its ability to safeguard retirees from financial insecurity.

Triple Lock Policy

The Triple Lock is a policy mechanism is designed to correct this inadequacy, by ensuring that the state pension increases annually. It guarantees that the state pension will rise by the highest of three measures: wage growth, price inflation (measured by the Consumer Prices Index, CPI), or a flat rate increase of 2.5%.

This system was introduced in 2010 with the aim of providing financial security for retirees and ensuring that their pensions maintain purchasing power over time.

This combination is intended to provide a safety net for older adults, promoting financial stability and reducing poverty among pensioners—which it has failed to deliver.

Criticisms of the Triple Lock

Despite its intentions, the Triple Lock has faced several criticisms primarily concerning its sustainability and impact on public finances.

Budgetary Pressure

Critics argue that the Triple Lock places significant pressure on government budgets, especially during periods when wages are rising rapidly or inflation spikes. This can lead to substantial increases in pension expenditure that may not be sustainable long-term.

Intergenerational Equity

There are concerns about fairness between generations; as pensions rise significantly under this scheme, younger taxpayers may face higher burdens to fund these increases through taxes or reduced public services.

Economic Viability

Some economists question whether linking pensions directly to wage growth is appropriate given varying economic conditions. For instance, if wages grow due to a tight labour market but productivity does not improve correspondingly, this could lead to unsustainable fiscal policies.

Political Manipulation

The Triple Lock has also been criticised for being politically motivated; governments may be tempted to adjust or suspend it during fiscal crises or elections based on political expediency rather than sound economic principles.

These criticisms highlight ongoing debates about how best to balance adequate support for retirees with broader fiscal responsibility.

International Comparisons

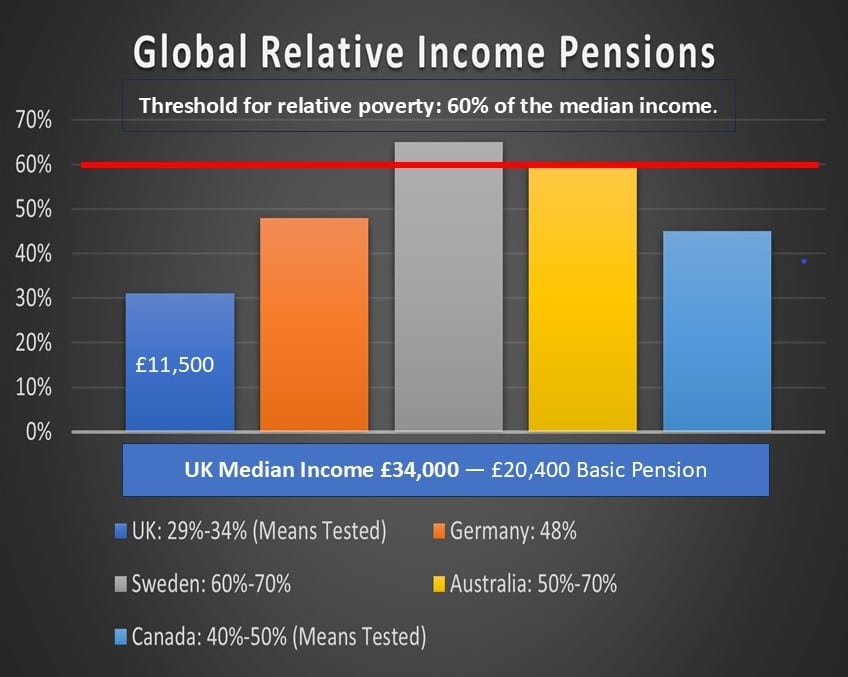

When comparing the UK’s state pension levels with those in leading economies such as Germany, Sweden, Australia and Canada, several factors come into play regarding adequacy relative to average wages.

Pension Levels Relative to Earnings

The UK state pension is relatively modest compared to some other countries. For example, as of recent data (2023), the full new state pension in the UK is approximately £220 per week (£11,500 annually). In contrast, Germany’s public pension system provides benefits that can replace around 48% of pre-retirement earnings after 45 years of contributions.

Level of Income Deemed as Poverty in the UK

In the United Kingdom, poverty is typically assessed using relative income measures. The most commonly referenced threshold for relative poverty is set at 60% of the median income.

According to the latest data from the Office for National Statistics (ONS), as of 2023, the median income for individuals in the UK was approximately £34,000 per year.

Therefore, 60% of this amount would be around £20,400 annually. This means that pensioners earning less than £20,400 are considered to be living in relative poverty.

Click caption to view chart — click to return

Median UK Income £34K 60% Pension = £20,400

Annual Pension £11,500 Underpaid £8,900

Over 75s who paid more into the system, expecting more than the Basic Pension, receive less — It’s a Scandal, or Is It Me!

Rethinking Pension Adequacy and Sustainability: Lessons from Global Models

Examining pension adequacy and sustainability reveals significant disparities between the UK and other nations, highlighting the need for reforms that ensure financial security for retirees while maintaining long-term economic viability.

Pension Adequacy

The OECD defines adequate pensions as those providing at least 70% of pre-retirement income for individuals with average earnings over their working life.

While the UK’s Triple Lock aims at maintaining purchasing power for retirees, it does not necessarily ensure that pensions are adequate relative to average wages when compared internationally.

Impact on Poverty Rates Among Pensioners: Countries like Sweden and Denmark have robust welfare systems that complement their pensions more effectively than in the UK. As a result, they often report lower rates of poverty among elderly populations compared to those relying solely on state pensions in Britain.

Global Sustainability Models

Other countries have adopted innovative models for adjusting pensions based on demographic changes and economic conditions, offering potential lessons for the UK. While many nations face sustainability challenges similar to those under the UK’s Triple Lock, some have implemented systems that may provide more balanced and adaptive solutions.

Sweden, for instance, employs a model that automatically adjusts benefits in response to demographic shifts. As life expectancy rises, the retirement age can be adjusted to ensure financial sustainability without compromising the system’s integrity. This proactive approach balances demographic realities with economic stability.

Canada’s pension system, akin to Australia’s and Sweden’s Notional Defined Contribution (NDC) model, is structured around multiple components. Programs like Old Age Security (OAS) and the Canada Pension Plan (CPP), complemented by private savings mechanisms such as Registered Retirement Savings Plans (RRSPs), create a comprehensive framework. This model is designed to meet the immediate needs of retirees while addressing long-term challenges posed by an aging population and fluctuating economic conditions.

These international approaches demonstrate strategies to achieve sustainable and equitable pensions. They will be explored in greater detail in Article 8, offering insights that could inform reforms to the UK’s pension system.

A National Scandal: UK Pensioners in Poverty

In summary, the UK’s Triple Lock provides limited protection against inflation and wage stagnation, yet it fails to address the glaring inadequacy of state pensions. With the full state pension at just £11,500 annually—and even less for those over 75—UK pensioners are left far below the relative poverty threshold, defined as 60% of median income (£20,400). This leaves countless retirees, particularly those without significant supplementary income, struggling to cover basic needs in one of the world’s wealthiest nations.

It is a scandal that pensioners in the UK face such financial hardship when compared to their counterparts in countries of similar economic stature, where pensions are more robust and complemented by stronger welfare systems. Immediate action is not just a matter of policy but of justice. The UK must reform its pension system to align with international standards, ensuring both adequacy and sustainability to protect its aging population and restore dignity to retirement.

Fourteen years of Conservative governance have eroded pensioners’ financial security, compounded by the Reeves Budget, which worsens the situation by freezing personal allowances, increasing the tax burden on pensions, and cutting key payments.

Is this system equitable, fair, or morally justifiable? The answer demands urgent reflection and reform, or Is It Me!

Next in the Series: Demographic Inequities in Pension Provision

Join Anthony Royd in the next instalment of this series as he delves into the deep-seated inequities in pension provision across demographic groups. Discover the factors driving significant disparities, particularly those impacting women, ethnic minorities, and single parents, and explore a compelling call for fair and lasting reform.

Please support this mission. It has the potential to bring transformative change and ensure a more just and equitable system for UK pensioners. By raising awareness and pushing for reforms, we are giving voice to those who have contributed to society, but are now facing undue hardship.

When we succeed, countless pensioners will gain the security and dignity they deserve in retirement—an achievement that will resonate for generations, or Is It Me!