Chagos Archipelago Betrayal! and Compensation

Published 21st December 2024

On October 12th, I raised concerns about Keir Starmer’s decision to hand over the Chagos Archipelago, warning that this move risked triggering a global security crisis. With just a small garrison, China could neutralise U.S. dominance in the Indian Ocean—potentially within weeks.

Diego Garcia is not merely a UK asset; it is a linchpin of international security. Yet, this decision, made without parliamentary debate, disregards critical principles of national security, democratic accountability, and parliamentary sovereignty.

In this commentary, I will examine the forced removal of the Chagossians and expose the inherent weaknesses in Mauritius’s territorial claim. The foundation of their claim rests on a Formal Fallacy—a flaw in reasoning that, as I will show, undermines its legitimacy and demands urgent scrutiny.

We must act now to prevent the betrayal of an overseas British Territory, or Is It Me!

Anthony Royd

Claims of Mauritius

A Case for Compensation and Sovereignty Reconsideration

The removal of the Chagossian people from the Chagos Archipelago and the subsequent claims by Mauritius over the territory represent complex and intertwined issues of colonial administration, decolonisation, and human rights. This commentary argues that the removal of the Chagossians was executed with scant regard for their wellbeing, necessitating compensation for the affected population.

Simultaneously, it critiques Mauritius’s territorial claim as fundamentally flawed due to the fiduciary nature of its historical administrative relationship with Britain.

Historical Context of the Chagos Archipelago

The Chagos Archipelago, a remote group of islands in the Indian Ocean, was part of the British colony of Mauritius until 1965, when it was separated by the British government during the era of decolonisation. This separation facilitated the establishment of a significant military base on Diego Garcia, one of the islands. In the process, approximately 1,500 Chagossians, descendants of enslaved Africans brought to the islands to work on coconut plantations, were forcibly removed from their homes. They were relocated primarily to Mauritius and the Seychelles, where they faced immense social and economic hardships.

This forcible removal, widely criticised for its inhumane execution, underpins the Chagossian claims for compensation.

Simultaneously, the detachment of the Chagos Archipelago from Mauritius has sparked a long-standing territorial dispute, with Mauritius asserting sovereignty over the islands based on its pre-1965 administration.

Legal Principles of Colonial Administration and Ownership

Colonial administration operates under a framework where administrators act as agents for the imperial power that owns the territory. In the case of the Chagos Archipelago, Mauritius’s role as administrator before 1965 does not confer ownership rights. This relationship was fiduciary, meaning Mauritius managed the islands on behalf of Britain, the sovereign authority.

Moreover, Mauritius’s claim fails to account for the principle that administration does not equate to ownership. Instead, administrators act in the interests of the owning power (Britain), making Mauritius’s claim a formal fallacy. Its argument assumes that administrative control automatically transforms into territorial sovereignty post-independence, which is inconsistent with established legal principles.

Decolonisation and the Fallacy of Mauritius’s Claim

Decolonisation

The decolonisation process involves respecting territorial boundaries unless mutual agreement dictates otherwise. While Mauritius asserts its claim aligns with decolonisation principles and self-determination, this argument is weakened by several factors:

Geographical Distance

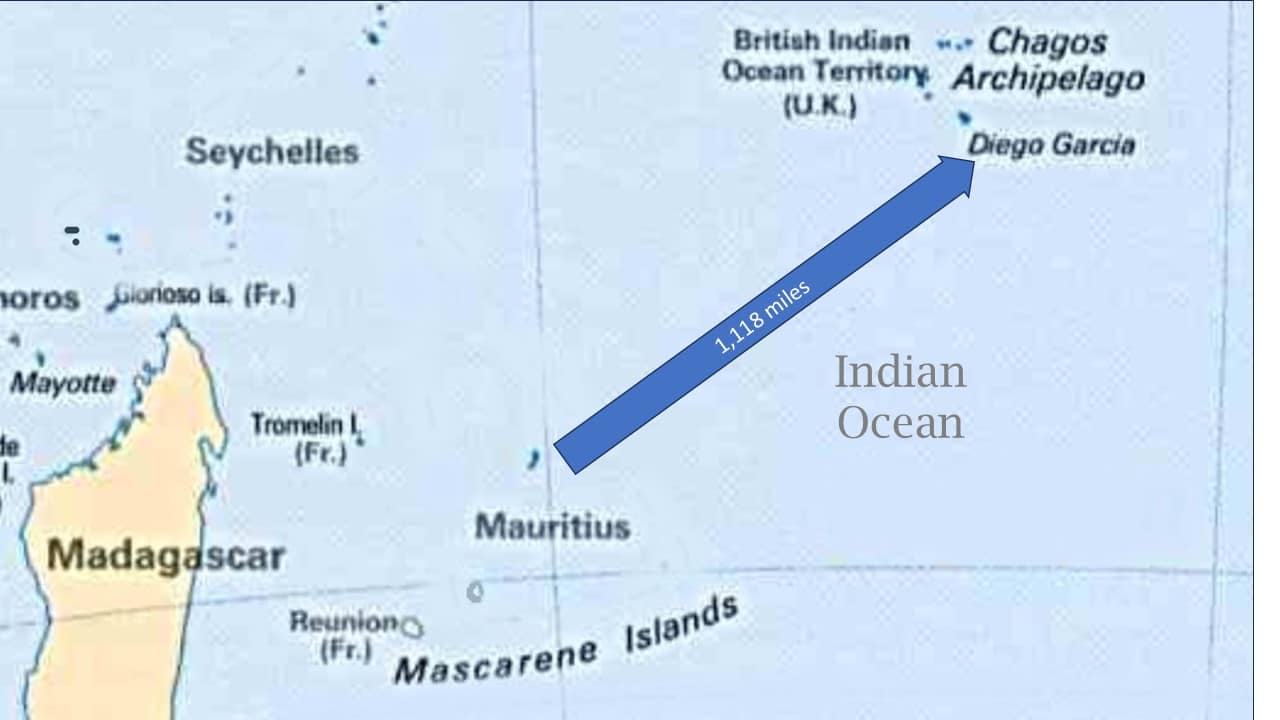

Mauritius is approximately 1,118 miles from the Chagos Archipelago, underscoring the distinct geographical and administrative identities of the two territories.

Non-Indigenous Population

No indigenous Mauritians resided on the islands. The Chagossians were the established population at the time of decolonisation, making Mauritius’s historical connection to the islands tenuous.

Mauritius 1,118 miles from the Chagos Islands

The Fallacy of Mauritius’s Claim

Fiduciary Relationship

As established, Mauritius’s role was as an administrator, not an owner. This distinction is fundamental to understanding the fallacy in Mauritius’s claim.

Although Mauritius’s argument resonates with contemporary decolonisation rhetoric, it overlooks the legal and historical nuances distinguishing administrative authority from sovereign ownership. While international courts have favoured Mauritius in their advisory opinions, these decisions lack binding authority, and the British Parliament remains the ultimate arbiter of sovereignty.

The Chagossian Case for Compensation

The removal of the Chagossians was conducted with scant regard for their welfare. Despite this, the British government at the time acted in ‘good faith,’ believing the actions served strategic and geopolitical interests. The displaced Chagossians faced significant hardships, including social and economic displacement, loss of cultural identity, and enduring marginalisation in their host countries.

Compensation for the Chagossians is justified on several grounds

Human Rights Violations

The forced removal violated fundamental human rights, leaving the Chagossians in impoverished conditions.

Historical Accountability

Modern norms of justice demand reparations for populations wronged by historical injustices.

Legal Precedents

Courts have acknowledged the plight of the Chagossians, albeit without mandating binding reparations, leaving room for moral and political redress.

The argument for compensation stands independent of Mauritius’s sovereignty claim. While the Chagossians’ grievances are rooted in displacement and human rights, Mauritius’s claim hinges on territorial sovereignty, making these two issues legally and morally distinct.

Conclusion

The removal of the Chagossians from the Chagos Archipelago was a grave injustice executed with insufficient concern for their wellbeing. This warrants compensation to address the harm inflicted upon the displaced population.

At the same time, Mauritius’s territorial claim fails due to the fiduciary nature of its administrative relationship with Britain. The principle that administration does not confer ownership undermines Mauritius’s argument, rendering it a formal fallacy. While international legal opinions have favoured Mauritius, these remain advisory, with ultimate sovereignty determined by the British Parliament.

Compensation for the Chagossians and the rejection of Mauritius’s territorial claim are not mutually exclusive, but reflect distinct legal and moral imperatives. Addressing these issues requires balancing historical accountability with the principles of sovereignty and justice.

Chagos Betrayal — Why Is the UK Government Silently Handing Sovereignty to Mauritius Without Scrutiny?

Now is the moment to expose the flawed foundation of Mauritius’s territorial claim—a formal fallacy that not only risks undermining international security and democratic integrity but also demands critical scrutiny. Why did the Foreign Office fail to advise the previous government of this fundamental flaw and prevent such a dangerous course of action? Why didn’t the Prime Minister recognise the fallacy in Mauritius’s argument?

Sir Keir Starmer, a lawyer with a distinguished career, was appointed Queen’s Counsel (now King’s Counsel) in 2002, an honour reserved for senior barristers recognised for their excellence in advocacy. From 2008 to 2013, he served as the Director of Public Prosecutions (DPP) and Head of the Crown Prosecution Service (CPS). His legal expertise makes the failure to identify and address the fallacy even more troubling.

Furthermore, why have Sir Keir Starmer and the Foreign Secretary, David Lammy, appeared so eager to avoid parliamentary scrutiny? — Could it be because they recognise that Mauritius’s claim lacks validity? Or does the timing of this change—coinciding with the Christmas and New Year parliamentary recess—reflect an intentional effort to facilitate the transfer without proper oversight?

These questions demand answers, as they suggest that something is seriously amiss within the Foreign Office and Cabinet Office. Is this an oversight, or is it something more deliberate? Either way, it warrants immediate attention and transparency, or Is It Me!